Names: The Legend of Zelda: Four Swords Adventures

Developer/Publisher: Nintendo

North American Release: June 7, 2004

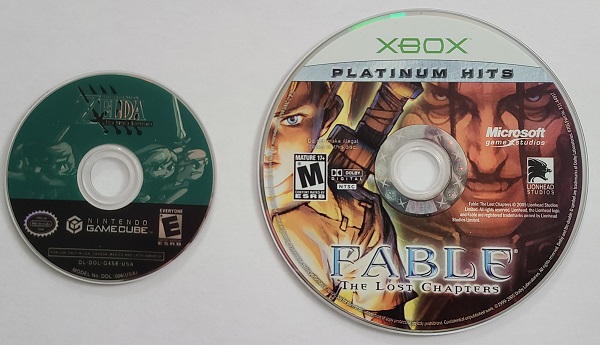

Console: Nintendo GameCube

Before we get into our piece for today, I’m going to take a moment to plug my fantasy books. This is my primary writing outlet, with these reviews being a way to branch out a little. However, Gold & Steel is where I do most of my writing. If you like your fantasy with only a pinch of the magical and stories driven the characters themselves, then Gold & Steel might be just for you. Get them from Amazon right here. If you want to give back in another way for the reviews, we also have a Buy Me a Coffee.

Also, it’s come to my attention that many of the images won’t work if you’re using mobile view on your phone. If viewing on a phone and you want the full experience, I recommend desktop view.

With that said, let’s get into it.

Normally with these reviews I like to open up with a little history about the game (or series), its IP, and the developer/publisher when said history is interesting and/or little known. This time, we’re going to abbreviate a little, because in this article we’re looking at a game from The Legend of Zelda series. Behind only the globally known Super Mario series, the worldwide phenomenon that is Pokémon, and the Wii console’s Pack-in title franchise Wii Sports, the Zelda series sits as the fourth biggest IP in Nintendo’s absolute fleet of titles. That’s no small feat, especially when you consider that it’s beating out other huge in-house franchises like Animal Crossing, Metroid, Super Smash Bros., and Donkey Kong, and by a wide margin, too.

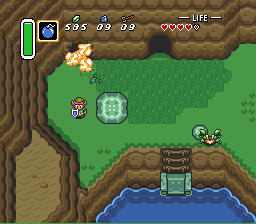

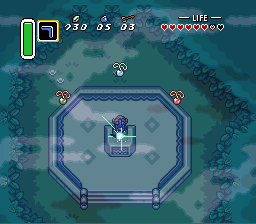

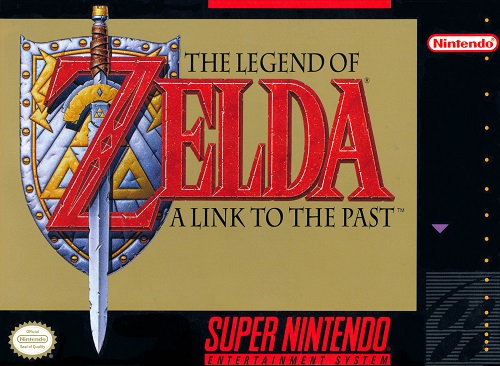

It stands to reason then, that the Zelda series needs no introduction. Given that, I won’t start from the beginning. Instead, I’ll start in April of 1992, just eight short months since the release of the Super Nintendo in North America. After two successful outings on the Nintendo Entertainment System, or NES, or the original/regular Nintendo, as it was often colloquially known in its day, the Zelda series followed Mario over to Nintendo’s entry into the 16-bit era: the Super Nintendo. It is here, with what would be the sole SNES Zelda entry that we start, with the third game in the Zelda franchise: The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past.

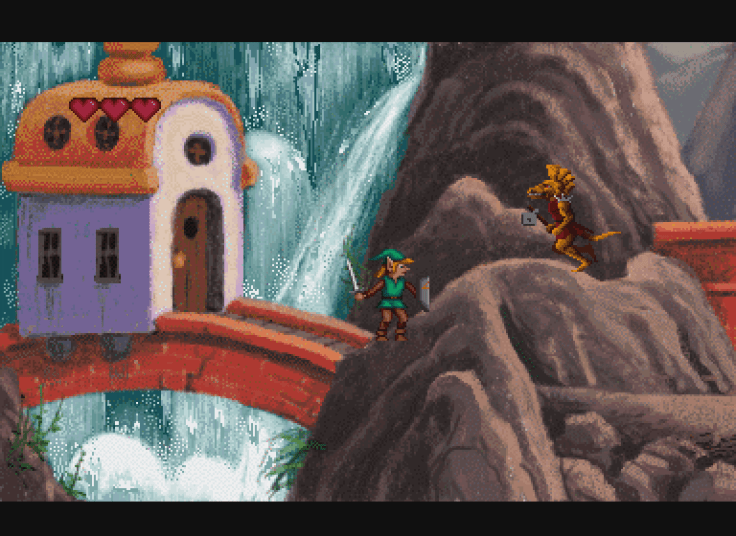

A Link to the Past (often abbreviated to ALTTP) brought The Legend of Zelda to life in a way that the NES was simply incapable of doing. The first Zelda game mastered the top-down adventure style and built a template that game developers in the genre have followed ever since. The Hyrule (the land in which most Zelda games takes place) of the first Zelda was a barren land inhabited almost solely by monsters. The human population was limited and disparate, hiding out in caves and dispensing a single line of dialogue each. While the land was a trip to explore in itself, especially for a game made in ‘87, it was otherwise lifeless and post-apocalyptic. The second entry, Zelda II: The Adventures of Link, was a departure from the first game in nearly every way. The game relied on an overworld map, (similar to what Dragon Warrior and Final Fantasy were doing) to get Link about from place to place and all the action would then take place on side-scrolling areas that felt more like Metroid or CastleVania than the first Zelda game. There were towns to visit now, the story was deeper, and Hyrule never felt larger, but still, it completely overlooked what made the first Zelda so much fun. It would go on to gain a reputation as one of the least popular Zelda titles, but that’s not to say it’s a bad game, because there’s no such thing as a bad Zelda game.

Rather, it’s an Action RPG game in a Zelda candy coating that today seems wildly removed from the typical 2D Zelda game formula. At the time, it didn’t seem as different because while it was different from the original Zelda game, there was no formula per se beyond the expectations that the first game set. It was still Link saving Zelda from Ganon, but Nintendo just decided to go in a wildly different direction with the gameplay from what they had already done. It looked and sounded fantastic for a NES game and handles smoothly. It’s much more difficult than the original Zelda, and in my opinion the hardest Zelda game in the whole series, but there’s much more difficult NES games out there and that’s even if you don’t count games that are unintentionally difficult due to bugs, shoddy game design, or poor controls. For all of that, Zelda II was a hit in its time and has aged better than many of its contemporaries. Even so, it still went on to gain a reputation as the black sheep of the mainline Zelda series.

Both games hit markets about a year apart from one another, with the original Legend of Zelda releasing in Japan in 1986 and North America in 1987 and Zelda II following it in 1987 and 1988 in the same respective markets. It was around this time that Nintendo’s management began noticing their 8-bit NES’s overall market share beginning to slip to Sega’s 16-bit Genesis console. Despite the success of their NES console and its related franchises, Nintendo knew it was time to think about the future, and it turned its focus to the next generation. In November of 1990 in Japan, Nintendo introduced the Super Famicom console and Nine months later, in August of 1991, it arrived in North America as the Super Nintendo. Nintendo sent it out into the world with a new Mario game, Super Mario World, and two new IPs that were created to highlight the fancy, 3D-ish, SNES exclusive Mode 7 tech: the futuristic racer, F-Zero and the aeronautical simulator, Pilotwings. Heading into holiday season ’91, Link was absent, but Nintendo hadn’t forgotten about the little guy in green. On the contrary, they were working on something big.

Nintendo had been working on a new Zelda title even before the SNES, starting the project all the way back in ’88. However, with the aforementioned decision to begin the move to 16 bits, Nintendo’s management rightly figured that a franchise that delivered 10,890,000 in sold units across just two games (big numbers at the time) should get as early an entry onto the new console as possible, and big, sprawling adventure games aren’t made overnight. That goes doubly so when your standards are as high as Nintendo’s. The developers of the third Zelda game missed the chance for Link to join Mario, Captain Falcon, and the Pilotwings… Uh… pilot, at the SNES starting line, but they didn’t miss that mark by much. In fact, in Japan, the third Zelda game went on sale by November of ’91 and had a fairly quick (by the standards of those days) turnaround time to reach North America, hitting the markets in April of ’92.

A Link to the Past brought players back to Hyrule via the familiar top-down vantage point of the first Zelda game, but with all the shiny, new gameplay and graphics that the SNES was capable of. Hyrule had life to it, with characters all over the place helping to guide Link through the land and the narrative. The colours were bright and lively; the settings varied from the lush forest, to a barren desert, the highs of Death Mountain, and the waters of Lake Hyrule. The dungeons and other submaps were more varied than ever before and Link had more tools at his disposal with which to navigate the puzzles and challenges. The music is some of the best on the SNES and uses the console’s tech to its utmost to emulate a full orchestra. In fact, as far as the music goes, much of what has become the core Zelda soundtrack is established right here in A Link to the Past.

Best of all, the developers introduced a Zelda staple in an attempt to double the game size: a second world for Link to travel through that happens to be an alternate dimension of Hyrule. In A Link to the Past, Zelda and the other maidens of Hyrule find themselves kidnapped by the wizard Agahnim and sent to the Dark World, where Ganon was banished prior to the start of ALTTP. Link must then travel there to rescue them and destroy Ganon. In a bit of real tech wizardry, that Dark World is in fact just an overlay on top of the existing main game, and the overall layout of the Dark World looks virtually the same as Hyrule. This bit of trickery seemingly doubles the game world in size, and though the actual map is just a re-skin of the first map, the changes from world to world are enough that it doesn’t ever feel like the simple overlay that it is. As far as gamer and critic reaction went, the technique worked, and combined with everything else Nintendo had jam packed into the 1 MB-sized cart, it resulted in A Link to the Past becoming a smashing critical and commercial success.

As far as home consoles went, this would be the last 2D Zelda entry for quite some time. By the mid-90’s, as I covered in other reviews like the Donkey Kong Country and Grandia write-ups, most video game publishers began or were well into exploring the mediums of 3D video games. Nintendo were no different in this regard, and were hard at work not only making rudimentary 3D games like Star Fox and Stunt Race F-X with the aforementioned Mode 7 chip for the SNES, but also looking at what their next console would be capable of doing. Much like Super Mario, Zelda had established itself as one of Nintendo’s primary flagship IPs, and nothing could be rushed out the door when it came to either series.

Starting as early as ’94, Nintendo began dropping hints about their entry into the 32/64 bit consoles. Just as was talked about in the Grandia piece, Nintendo had initially been working with Sony on a disc console, but things ultimately petered out. Phillips came on board with Nintendo instead for a loose licensing deal for their CD-i console, but their mediocre showing with the system left little to be desired. As a result of both that and lagging sales of rival disc consoles of the time, like the Sega CD add-on for the Genesis, the Atari Jaguar’s CD add-on, and the Sega Saturn (Sega’s first attempt at a stand-alone disc console) Nintendo were left ultimately unimpressed with discs as a medium of delivering entertainment. They decided that their best bet was to stick with the cartridges that brought them to the dance and thusly, they unveiled their contribution to the next generation of consoles: the Ultra 64. Within a year, it would be renamed Nintendo 64, but either way, Nintendo’s plan was clear: 3D gaming via cartridges.

From the moment this was announced, the Zelda series was second only to Mario in terms of fan interest, but unlike the near-immediate announcement of Super Mario 64, Shigeru Miyamoto (the general manager at Nintendo and perhaps the most esteemed legend of the video game world) would only say that they planned to bring Zelda to the new console. In the meantime, fans would have to stick with the three Zelda games they already had across Nintendo’s home consoles… Or, they could sink their teeth into a Zelda game for the Game Boy.

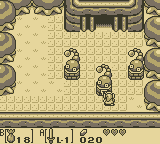

Hitting shelves worldwide during the summer of ’93, The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening marked the Zelda series’ first appearance on a handheld console and the fourth game in the series overall. The Game Boy as a console was certainly not the most powerful handheld system, not even for its time, and it required developers to downsize its games from SNES and even NES standards. Still, Nintendo saw that as no obstacle and just as they’ve proven before and after, no one knows how to get the most out of their hardware like Nintendo. Not only was Link’s Awakening no exception to that rule, it set the standard for sheer quality that was capable for a Game Boy title.

Given the hard limits of the Game Boy’s tech, Nintendo made the decision to extract Link from the land of Hyrule for the first time, depositing him on the mystical island of Koholint. The smaller (although probably not as small as you think) game area is rendered using as close a facsimile of A Link to the Past’s aesthetics as the Game Boy’s hardware could possibly manage. This limit-pushing game left its mark with both critics and consumers as it would rack up awards and accolades such as a Golden Joystick award for Handheld Game of the Year and a sweeping run of Nintendo Power’s yearly reader-voted awards in the Game Boy categories in ‘93. In nostalgic polls and lists, it even still consistently ranks amongst the top Game Boy games, usually beaten only by the Pokémon titles.

The game didn’t re-invent the wheel, but it did make a few modifications to the formula that A Link to the Past refined. For instance, it allowed itself a level of humour and charm that was mostly absent from previous Zelda games. At the same time, it didn’t skimp on storytelling, and has a surprising amount of emotional depth for a Game Boy Action-Adventure game. Given that the Game Boy only had two buttons to work with, compared to the four face buttons and two bumpers on the SNES, it also had to modify how Link used and stored items. In A Link to the Past, Link had the B-button solely for his sword, and his shield was at a default ready-state. The secondary items, like the bow, boomerang, and hookshot, could be swapped for one another on a menu screen and then used with the Y-button. Functions like lifting items, talking, and dashing were mapped to the A-button.

Link’s Awakening had to work with less, so it made the A-button the interaction button and then put every usable item into your inventory to be freely assigned to either the A or B buttons. That meant that Link could un-equip the sword and shield and hold any random combination of items, like say the Roc’s Feather (which allows Link to jump, a first in the top-down Zelda games) and the Pegasus Boots (which allows Link to dash) allowing Link to perform a running jump. This mix-and-match system was used to its fullest too, with several puzzles and dungeons requiring such trial-and-error item swapping to find the best combination of items for any one task. Though this system was obligatory due to the limits of the Game Boy, it didn’t hinder the game, and in fact, it set it apart as unique from A Link to the Past.

After the success of Link’s Awakening in ’93, Nintendo would make no further Zelda games in 2D for a number of years. However, in 1998, with the not-quite-a-full-new-console Game Boy system called the Game Boy Colour, Link’s Awakening got a re-release, which was a rarity in the 90’s. This time, the game is fully colourised, given a few select additions, and sent back out into the world as Link’s Awakening DX.

Over on the home console front, the Zelda series was changing the video game world. I’m not going to get in to Ocarina of Time or Majora’s Mask with any sort of detail, but for the purposes of this piece, I will say that to say that Ocarina of Time was a success would be an understatement. Nintendo delivered on a big, beautiful adventure game in 1998, and they nailed every facet of it along the way. It would go on to rank in as the fourth best-selling Nintendo 64 game, beaten by only Super Mario 64, Mario Kart 64, and Goldeneye 007 respectively; it would win numerous video game awards, and achieve critical and consumer praise for decades after.

Majora’s Mask followed in 2000 and used the same engine as Ocarina of Time and most of its graphical assets, but came with a new setting and a few other quality of life additions. Its story and sub plots were more developed than Ocarina of Time, but it was an overall slightly smaller game and was held to a repeating in-game three-day cycle that turned away some players. It still achieved critical and commercial success, but Ocarina of Time generally remains as the overall go-to Nintendo 64 Zelda experience. Personally, I preferred Majora’s Mask over Ocarina of Time, but I’m a huge fan of both games and have replayed them both beyond count. I could write separate articles on each one and how much I enjoy both games and in the future, I just might. For now though, and for the sake of getting on with this particular article, we’ll leave those two games alone. What it means to this piece though, is that Ocarina and Majora’s signified that Nintendo was taking the Zelda series to the 3D realm on the home console, and that was the future as they saw it.

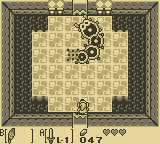

However, 2D Zelda titles weren’t done, they were just shifted to the Game Boy Colour, which was gifted not one, but two Zelda games at the exact same time, and there was a reason for that. You see, Pokémon had arrived just a few years prior in North America, and its initial Red and Blue releases were smash hits. The two games were identical save for the roster of Pokémon a player could collect in either entry. To collect all 150 Pokémon, a player would need someone with the other version of the game and one of them would need a link cable to trade Pokémon back and forth. It was an obvious money grab, but players bought the games up anyway, proving to Nintendo that such blatant marketing ploys could sell with minimal pushback. With that in mind, Nintendo decided the next series that needed a pair of companion games was Zelda. Capcom were given the reins to make the pair, and in 2001, they hit store shelves under the names The Legend of Zelda: Oracle of Ages and Oracle of Seasons.

The games were instantly familiar to anyone who had played Link’s Awakening, as they were built using the same engine and man of the same assets. They played, sounded, and looked like a minor upgrade to Link’s Awakening, but the truth was that Capcom and Nintendo managed to pack two full, separate games into those tiny Game Boy packs.

Unlike the Pokémon games, which were merely different versions of the same game that required cross-play to fully complete, the Zelda: Oracle games were their own separate adventures that could be finished separately, but had some extra content for players when the games were (pardon the pun) linked.

The games took place on two entirely different maps, with each one having certain unique items for Link to use, different characters to interact with, and different dungeons and puzzles to solve. It really was a double game experience. The bonus content for linking was interesting enough in its own right, but it neither made nor broke the overall experience of playing either game. Think of the bonus stuff as a precursor to free DLC content or a little bonus material for having bought a “deluxe” version of the game.

The games proved popular and collectively landed in twelfth place for sales amongst all Game Boy games, not just Game Boy Colour games. The only games that beat it are Pokémon and Mario titles, Tetris, Kirby’s Dream Land, and Link’s Awakening (when you count the sales of both the original and DX versions, that is). That’s pretty prestigious company, especially when you consider that the games came at the tail end of the lifespan of that iteration of Game Boy consoles.

While the Oracle games certainly didn’t revolutionise the standard when it came to Zelda games, they were both excellent games and well worth players’ time. More importantly for the topic at hand though, they proved that 2D Zelda games were still popular, despite the fact that the two Nintendo 64 Zelda games had taken the gaming world by storm.

It was around this time that a new generation of home consoles began hitting the market, and the aforementioned Nintendo 64 was starting its walk into the sunset. Up until now, Nintendo had been the lone major console company to hold out on the switch to disc media, stubbornly wanting to stick with cartridge systems. (You can read more about that over at my Grandia review) One of the leading reasons for doing so was that (at the time, anyway) pirating cartridge games was exceedingly more difficult than pirating disc games, and both the Sony Playstation and PC markets were rife with examples of how easy it was to bypass the security measures of the time. The Nintendo 64 was also a laborious effort for developers to even program games for, let alone the process of reverse engineering them for piracy. Nintendo were proud of their accomplishments in keeping their consoles and games out of reach of pirates (at the time), but they soon realised that their anti-piracy efforts were ultimately both short sighted and futile.

The reason for that was even though Nintendo’s carts were good on the anti-piracy front they were lacking on the data storage side in those days. Data card storage, which is essentially what a cartridge is, just could not keep up with both the storage and processing demands that the next generation of games required. Sony, for instance, had already outgrown the CD format of the PS1 and were moving on to the DVD format for their PlayStation 2 console. Microsoft skipped CDs altogether and went straight for DVDs with their first foray into consoles: the original X-Box. Sega thought outside the box for their Dreamcast console and came up with their own, uniquely engineered disc format called GD-ROM that allowed for a full gigabyte of storage (believe me, youngsters, that was huge for the day) on one CD. Likewise, Nintendo knew they had to follow suit. It was discs or bust. If not for the above reason alone, it was simply an economic decision, as cartridges were incredibly and increasingly expensive to manufacture compared to discs. Nintendo had a compromise, though, and it set them apart in this generation of consoles: their own format that was the same size as a mini DVD.

Thus was born the Nintendo GameCube, continuing Nintendo’s efforts to thwart piracy and inadvertently annoy third party developers. Compared to the 4.7gb DVD discs used by Sony and Microsoft, Nintendo’s unique discs could only hold 1.46gb of data. The size difference made porting games made for the PlayStation 2 and X-Box to the GameCube a bit more cumbersome than it needed to be. The end result often meant cutting content from games outright, compressing video and music files, and/or other workarounds to get a serviceable port from titles that were otherwise relatively fairly straightforward on the PS2 and X-Box. Nintendo themselves, like in the N64 days, knew how to get the most out of their media and their own properties, with titles like Luigi’s Mansion, Super Mario Sunshine, Mario Kart: Double Dash, Metroid: Prime, Super Smash Bros. Melee, and new IPs like Animal Crossing and Pikmin utilising the comparative limitations of the hardware to make top tier games. By the first year of the console’s life, it even had a Zelda title: The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker.

This Zelda entry continued the 3D format that Ocarina introduced, but due to time and resource concerns, it eschewed graphics geared toward realism and shifted to a cel-shading animation style that looked like it was right out of a Saturday morning cartoon. The gameplay was largely an updated version of the engine that was used to make Ocarina and Majora’s on the N64, and handled similarly to both. The story was in the typical Zelda wheelhouse, seeing Link and Zelda attempt to stop the evil Ganon. However, this time, the entire thing took place within an archipelago on the sea and Link was required to cross the sea between locations in the game world at the mercy of the wind in a tiny sailboat. Instead of traversing over fields and hills with nooks, crannies, and secrets to discover, the player had what felt like a vast, but largely empty ocean divided into map squares. Sure, each square had at least something of interest there, be it an island or even just some enemy lookout posts; but it was still a big, empty sea and a tiny sailboat with which to traverse that endless blue. Granted, Link was given a conductor’s baton to control the wind, helping his boat move at its quickest in most directions and the ability to warp to certain locations eventually comes into play, but it still hindered the experience. Along with the graphics that I mentioned, it seemed like it might be a rare miss for Nintendo…

Swerve! It was actually a smash hit. Granted, with it being twenty years on, I’m sure that was not actually news to most readers. See, while some Zelda fans didn’t like the graphics, and the open sea was a bit of a drag, the gameplay and story were in top form, and it proved to be a wholly playable and enjoyable time from start to finish. It was also the most open of Zelda titles up to this point, allowing Link to navigate the whole map fairly early into the games. The usual Zelda format, from the original Zelda game onward, had been to give the player a portion of the map at a time in which to explore, with a dungeon anchoring each area. Link would then either obtain an item within the dungeon that would overcome an obstacle that had prevented further travel, or some other action would take place at the entrance to the new region that would allow Link egress, and the game would move on. Wind Waker blew the doors off that and said, “Here’s a tiny boat and a baton for controlling wind directions. Go to it,” fairly early into the game. It was novel for a Zelda game, as such free roaming was not widely common at the time. Granted, the Elder Scrolls and Grand Theft Auto franchises (amongst others)existed back then, so open-world, sandbox games weren’t totally new, but it was new for the Zelda series, which usually relied on a game world that controlled its narrative to a certain point. Sure, there were certain islands that were inaccessible in Wind Waker at first, (usually because they contained dungeons intended for later in the game) so they did still have a certain amount of narrative sway over things, but it still allowed for far more exploration than any Zelda game before it.

At nearly the same time that Wind Waker dropped, Nintendo also released a remake of A Link to the Past on the Game Boy Advance, which was their newest handheld console. While seemingly innocuous enough, this was no mere tweaked remake, like Link’ s Awakening DX, oh no, this was actually two games in one.

This curious little game had the advertised LTTP remake, but it also came with a secondary game called The Four Swords. While the remake was its usual one player self, Four Swords did what no other Zelda game before did: it made Zelda a multiplayer experience. That’s right, you and a friend or three with a GBA and a copy of the game each, could link up and play a Zelda game together. No more over-the-shoulder, back seat driving, you were right there in the action with them… You know, so long as you all had copies of the game and GBAs. Still, for younger siblings everywhere, this was the first time they could get in on the game with that eldest sibling who always hogged the controller when the Zelda cart was in the console.

We’re not going to get into the details of that game, because everything it did was also brought forward into a much larger sequel. Nintendo had managed to try Zelda as a multiplayer game within the safety of a cart that was primarily marketed as A Link to the Past re-release. The game sold well, and the Four Swords side of things was well received, but it wasn’t fully its own thing. With the waters tested via A Link to the Past/Four Swords, Nintendo decided it was time to go all-in on making a multiplayer Zelda on not just a handheld system, but on the home console front.

Thus, two years after both The Wind Waker and A Link to the Past/Four Swords, Nintendo had a new Zelda game for the masses called The Legend of Zelda: The Four Swords Adventures.

From the first moment that the player presses start you know this going to be nothing like the Zelda games you’ve known before, because no other Zelda home console game has taken the time to ask you how many players there will be. The game was playable for one player, but you could also have between two to four players all join in at once. However, it’s not like the Smash Bros. Melee and Mario Kart: Double Dash parties that you know and remember from the Game Cube. Oh no, much like the other Four Swords, you need four Game Boy Advance consoles in addition to the Game Cube to play Four Swords Adventures. It’s the only game that requires five whole consoles (the Game Cube itself and the four GBAs) to play at full multiplayer capacity (not counting online games, which we’ll talk about), and that requirement is as every bit as ridiculous as it sounds. It gets even more ridiculous when you factor in that in order to connect the GBAs to the GameCube, a GameCube – Game Boy Advance link cable was also required for each GBA, and only one of those came with the original purchase of a copy of The Four Swords Adventures. That’s right, buy it used and you might have been crap outta luck. So, to recap, in order to play The Four Swords Adventures to its full, four player capacity, as was intended, you would require:

- One Nintendo GameCube console

- One copy of The Legend of Zelda: The Four Swords Adventures

- Four Game Boy Advance consoles

- Three GameCube – Game Boy Advance Link Cables (Four if your copy didn’t have one.)

That’s an impressive pile of hardware to play one multiplayer game. Remember, this was released in a time when MMORPGs (massive multiplayer online role playing games) like Everquest and RuneScape already existed for several years, PC games like the first person shooter series Quake and real time strategy series Age of Empires had multiplayer online capabilities, and even Sega had an online, four player RPG for their Dreamcast console that was ported to the GameCube with online functionality intact in the form of Phantasy Star Online. It’s not as if Nintendo would have been breaking new ground to make Four Swords Adventures playable online. It had been done up to this point, and on Nintendo’s own console, nonetheless. Remember, this is a console that already had four controller ports. Games like Mario Party 4 and Def Jam: Vendetta could be enjoyed by up to four people in the same room by just needing one console, one game, and four controllers. Just like much of the Nintendo 64’s library before it. Again, not a new thing. So, yeah, the requirements to play Four Swords Adventures in multiplayer are not only over the top by today’s standards, it was wild in 2004 too.

What remains to be asked is “Was it worth it?” and the answer to that is a firm no. It’s not worth all that expense to play The Four Swords Adventures. That’s not to say it’s a bad game though, it just says that the requirements for full multiplayer are far too costly to justify itself. The game is certainly worth playing, and luckily, as I mentioned before, it has a one-player mode, which is what my review is based on. The reason I say all that is because the game can be fully enjoyed as a single player experience, and the reason for that is as game developers, Nintendo are nothing if not dutiful in thinking of damn near everything. Since the arrival of the original The Legend of Zelda on the NES, the one thing that’s held true about the series is that they’re a solo experience. You, the player, have one controller and control one version of Link on the screen. The Four Swords Adventures starts you off with the Link of this particular story stuck in a dungeon without a weapon and in desperate need of one. He spots a nearby sword and plucks it from its pedestal, unleashing the power of what we find out is called the Four Sword. Its unique properties create three duplicates of Link, identical aside from the colour of their trademark tunics.

In four-person multi-player, that sounds all good. Each person controls a Link, and you go on your adventure. However, given the aforementioned solo nature of Zelda games and the ostentatious requirements to play said four-person multi-player, Nintendo knew it might be asking too much to let that gimmick carry the game, and Nintendo implemented a single player mode as well. In that mode, which I’ll be covering here, instead of merely controlling a single one of those four Links, the one player mode has you controlling all four, usually at once. It manages this by having them typically walk in a close line. In this line, the lead Link can do most functions that you’d normally do as Link in any of the other top down Zelda games. Link can walk, swing his sword, pick up small objects, roll forward, and jump downward to lower platforms or water, swim, and push, or pull objects that are too heavy to lift. You know, the standard Link stuff.

With that said, let’s look at how Four Swords Adventures separates itself… Or rather divides itself, in this case. With a press of the Y-button or a push in either cardinal direction on the c-stick, the Links will form up in lockstep in one of four possible formations: a horizontal line, a vertical line, a tight square with all facing in one direction, and a loose diamond where they stand back-to-back. Of course, all of those are oriented from the overhead perspective of the player and each one has a particular use in puzzle solving and combat. The horizontal and vertical lines serve the same purpose and allow for the Links to be able to push or pull large objects like logs or heavy levers and pulleys with ease. In combat, the lines will be most players’ regular choice, as they become the most powerful version of any Link this side of the Fierce Deity Link. Seriously, you’ll never clear a screen of enemies as quickly as you do with four Links lined up and swinging their swords or loosening arrows in unison.

In the square formation, the Links’ main function is lifting large objects, like boulders and statues. It’s a fairly useful combat stance too, as it’s like having double the slashing radius of a single Link. On the downside, you’re a bigger target for the enemy, but I feel like the pros outweigh the cons here. Lastly, there’s diamond formation. This formation has little puzzle application, and the combat use might not be immediately apparent beyond having four Links standing back to back, where they can have a sword slashing simultaneously in each base compass direction. However, do you remember how holding down the sword button in most Zelda games would cause Link to power up for a spinning slash? In the other three formations, the Links do just that: spin around in a circle in unison. Yeah, try that in diamond formation. The Links spin as one large circle, making for some serious cutting power. You can even power that up, too, but I’ll get into that later. All four formations can be rapidly switched using the C-stick, and there’re certain combat situations where quick changes can make a difference and lead to some exciting gameplay.

Apart from moving Links in a line or a formation, you can also navigate as a solo Link by pressing X. In this mode, three Links take a seat and you control just the one. Not very useful for combat, but as a puzzle device it comes up a few times in a few ways. For instance, you can lift and throw the other Links, which you can use for crossing gaps or reaching high and/or otherwise inaccessible platforms. Also as a solo Link, there are often switches that only a Link of a certain colour can activate or blocks to be pushed or lifted with the same colour-bound restriction, and you’d best believe they use these solo mechanics to their fullest. By continuing to hit X you can cycle through the four Links, while pressing the Y or L buttons in this mode draws the Links back together into a loose line, but I suppose, given that they’re Links, it would be more apt to call it a chain.

Now that you know how to get all your Links in a row (no pun this time, I promise), let’s look at how you use them to navigate the world of Four Swords Adventures. Usually, in Zelda games, you have a fairly open world. The first Zelda, for instance, was almost completely open. Go in any direction you want from the start, your only limit is the enemies on each screen and any walls or other obstructions to keep you from going too far out of bounds. Nintendo did this in all the previously mentioned top-down Zeldas (Zelda 2 notwithstanding, as it technically has a top-down map, but the map’s more akin to the early Final Fantasy games than its fellow Zelda titles, and the core gameplay is platforming) by cutting the map into sections that could be loaded and viewed on the TV screen. As you hit the far sides of the screen, the view would shift one TV-screen worth of space in that direction (again, as long as their wasn’t an obstruction) and plant Link in the corresponding place on the next TV-screen-worth of the map. Newer titles like A Link to the Past and Ocarina of Time barred access to certain game areas until you had a specific tool or key to remove the barrier. If you’re expecting any of that in Four Swords Adventure, though, you’ll be left wanting. This game goes in an entirely different direction (for a Zelda game, anyway) and instead borrows from its older, bigger cousin series: Super Mario.

Because the game was built with multiplayer as the main draw, the game just wasn’t able to do an open world like Zelda games before it (and after it). While several games, like the aforementioned Everquest and Runescape, did open-world, massively-multi-player games, the games are still meant to be played by each player on their own computer screen. Four Swords Adventure, meanwhile, as mentioned before, is a couch co-op game.In other couch co-ops, like Mario Kart, Goldeneye 64, and Halo, the screen splits in each player can view their gameplay in their quadrant. That’s fine in a game with an over-the-shoulder third person view like Mario Kart or a first person view like Goldeneye and Halo, but it leaves only a small playing area per-player for a split-screen, top-down view. Some games, like the Super Smash Bros. series, get by with having all players share one screen, but the players also stay on just one screen, so there’s no roaming, unlike in a typical Zelda game. Nintendo wanted players to be able to explore together, though. However, an open world where everyone had to stay on the same screen, without screen splitting, was a tough scale to balance. Solution: break the game up into stages, like Super Mario.

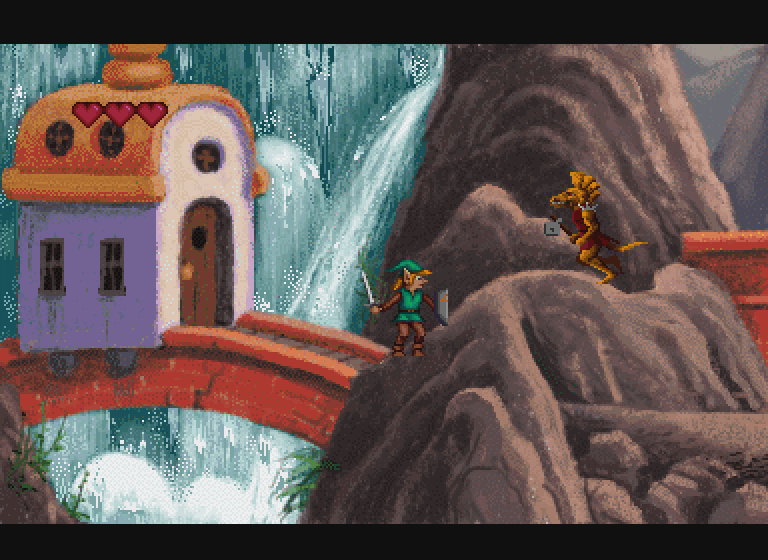

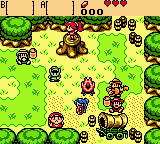

Most stages take place on open terrain, with assets lifted directly from A Link to the Past and enhanced with effects not possible in 1991 and cel-shaded animations similar to The Wind Waker thrown in for good measure to really make the game pop.

Usually, each stage is fairly linear, with each screen having but one natural entrance and exit. There are a few instances, such as in forest and desert stages, where things are a little more open and sometimes there’s backtracking due to cause-and-effect type puzzles, but they’re more of an exception than a rule. To wit, each screen will usually fall into one of three categories: puzzle, combat gauntlet, or a rest point of sorts. The first two are self-explanatory, and the third is usually just a screen where there are either non-player characters with which to interact, currency (but not rupees) to collect, hearts to replenish your health, or some combination of the three. The rest point screens might also have a few enemies or a trivial puzzle to solve as well. These stages are further divided into levels, with each one culminating in a dungeon much akin to what we’re all familiar with from the previous top-down Zelda games.

Apart from these screens, you’ll often find caves, underground passages, portals to the shadow dimension, and small buildings to enter. At this point you might be thinking, given what I’ve said about the screens and how it all ties in to multiplayer, “How’s that gonna work, Chris?” The answer is the reason why multiplayer requires a Game Boy Advance.

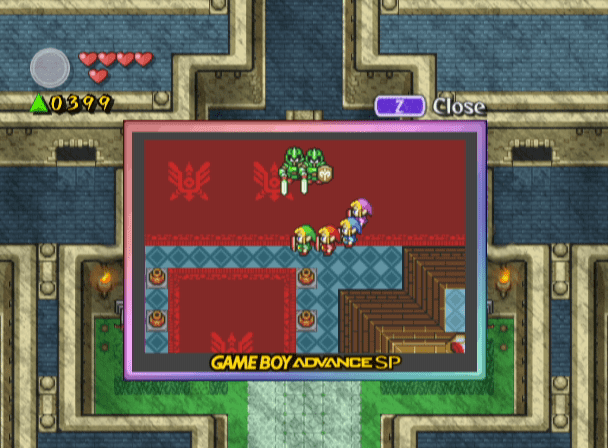

Every time you encounter an area-within-a-screen in single player mode, you’ll see a new screen pop up and overlay the actual screen you’re playing on. The first thing you’ll notice about the overlays is that the graphics are simplified and most of the special effects have been stripped away to SNES levels. That’s because these screens are actually made to be played on the Game Boy Advance in multiplayer. In that mode, the player who enters the area-within-an-screen will be directed to their Game Boy Advance screen, where their gameplay will continue. For most of these areas, all four players can enter and sometimes must enter. In other instances, it’s a solo journey. In these screens, the gameplay will either be top-down, like the gameplay on the main screen, or cleverly shift to a quasi-side-scrolling style just like in Link’s Awakening and the Oracle games on the Game Boy and Game Boy Colour.

Personally, I think the whole setup is ingenious. Nintendo, never ones to settle for mediocre to begin with, put the time and care into everything to make sure that it all performs without a hitch. Granted, levels and stages are a stark deviation in a Zelda game, but I found it to be an interesting twist on the norm that kept things in that sweet spot of being familiar, but also altered the formula enough so as to make something new and exciting.

While a more open, sandbox-style might be fun in multiplayer, Nintendo’s development team clearly wanted players to experience the whole game together with a clear start and end point. In that regard, I feel it’s a success. The game encourages players to progress through the stages, and while there is room to mess around and have aimless fun, I’ve found that things are intriguing enough that even the most easily waylaid player will be eager to move on pretty quickly and see what’s on the next screen.

In most Zelda games, Link’s ability to explore is usually made easier by finding things like heart containers to increase your life meter, rupees (Hyrule’s currency) to buy consumables and certain items, and tools/additional weaponry that you discover along the way. You might be asking what sort of items, besides the usual sword and shield, will be at your disposal for navigating the combat and puzzles, and the answer to that is once again another area where Nintendo’s development team took a unique approach to the Zelda formula. Usually, as mentioned earlier, all these items are assigned to one or two buttons on the controller and you have to pause the game to bring up an inventory screen to switch the item at Link’s disposal. That created problems for the multiplayer mode, though, because now players would have to be continually bringing up an inventory screen to switch items. Having players constantly pause to switch items is not conducive to the flow of the game. The other direction would be to give players the option to bring up an inventory screen on their GBA screen (or the main screen, in single player mode) and have action continue while they’re looking away. That’s also a problem, as now players could be left vulnerable to enemies and traps while they’re swapping out items. Then they have to worry about whether one player picking up an item puts it in everybody’s inventory or just that players, what happens if items are missed, and so forth.

Instead of all that, and rather than bog each individual player down with inventory, Nintendo decided that Four Swords Adventures would work better on an as-needed basis for tools/weapons, rupees, and heart containers. What that means is that you start the game with each Link having only a sword and shield, four heart containers, and no currency. That in itself is pretty much how you will play out the game. In each level, you can find heart containers to fill your hearts, and rupees… Wait, rupees aren’t triangular. Oh, yeah, that’s because they’re actually called Force Gems this time around. They have the same colourings and general aesthetic as rupees, but these work a little differently. As you progress through the level, you’ll find Force Gems in all the usual places that rupees typically are, such as in shrubs, in the ground, in smashy pots, dropped by defeated foes, and so forth. You’ll notice pretty much right away that this version of Hyrule is thoroughly littered in them, some might even worry that the sheer amount of Force Gems might cause hyperinflation and collapse Hyrule’s entire economy. That is by design (and not to cause hyperinflation), because in each level you’re encouraged to collect 1000 of them. At that point, your sword will power up, giving you the same abilities that a fully powered Master Sword would in A Link to the Past… And then some. Remember how I talked about the formations of the four Links? That aforementioned diamond formation with a powered up sword sends the Links flying all around the screen, clearing enemies with ease. Granted, Link will be a bit dizzy and vulnerable to attack at the end if you miss, but it’s usually worth the risk to do so because the swirling vortex of swords it creates doesn’t need much effort to strike an enemy. Like other Zelda titles, the currency is sometimes needed to buy consumable items and quest-related items on a level-to-level basis.

Heart containers are likewise fairly common in this game. Each level will have them scattered throughout, usually as a reward for solving a puzzle or beating an enemy horde. They’re only good for each level though, and your hearts will reset at the end of each level. Some may see this as a negative, but it makes sense, as it resets the playing field every time you replay a level. It’s not an RPG game, after all, (unlike say, Chrono Cross, my review of which you can read right there) where you’re trying to power up your character to tackle stronger enemies deeper in the game. The levels themselves reset after each completion, and Links and the enemies stay at the one power level throughout the game, outside of temporary power-ups that you may find. So stacking your inventory full of hearts, rupees, and tools are not needed at all to progress. That might be a deal-breaker for some and if so, fair enough. However, I see the sense in it, as it allows for a player or players to pick-up-and-play of any level without having to worrying about having enough of something or a certain item that might have been missed somewhere along the way in another stage or level. That’s because each individual level will ultimately give you enough of what you need, and often more than enough, to finish any level at any time.

Take staple Zelda items, like the bow and boomerang, for instance. If there’s a point in a level where you need a bow to shoot a switch that’s out of reach, or a boomerang to retrieve a key or such, and you don’t have that item on hand, then no worries. You know that somewhere within the map of that level is that item. Maybe you missed a cave or a small building a few screens ago, or you’ll need to grab a power bracelet first so that you can move a boulder out of the way to get to the bow or boomerang. The point is, what you need is going to be somewhere in the level.

There are also mini-games to be found in Four Swords Adventures, but they can only be played in multiplayer mode. Other than mentioning them, I can’t offer anything in the way of review, but I’d have been remiss if I left them out. Given the quality of everything else up to this point, there’s little reason to assume they’d be anything less than a great, fun time.

That brings us to the story. Well, I’m not going to mince words and make it out to be more than it is, because it’s the standard Zelda fare. An evil omen looms over Hyrule, Zelda (and her maiden friends) thinks the seal keeping the villain-of-the-day (in this case Vaati, the same one as seen in The Minish Cap) encaged is weakening. Zelda and pals grab Link and go to investigate and that goes about as well as it usually does for Hyrulian women of nobility. They establish in the greater Legend of Zelda lore that with some exceptions (Like from Ocarina of Time to Majora’s Mask), the Link and Zelda of each title are reincarnations of previous Links and Zeldas spread across centuries and they don’t share their memories or experiences. However, you’d think someone along the way, like the Sheikah line that protects the royal family and tends to keep records of everything, would know to teach every new princess named Zelda to not go anywhere near anything even vaguely suspicious.

As per usual, Zelda and the maidens are kidnapped, this time by a shadow version of Link. Link chases down said shadow and grabs a nearby sword from a suspicious place. Again, you’d think the Great Deku Tree or someone would council all the subsequent Link against taking swords they find in dubious locations. Yes, the Master Sword is indeed a sword found in the woods in a dubious location, but generally, it’s not a safe practice and frankly, Hyrule shouldn’t be depending on Link’s ability to find mythical weaponry to save it. Strange kids finding swords in the woods is no basis for national security.

I digress. Anyway, because Link grabbed that sword, Vaati is released, and once again, Hyrule is plunged into chaos. Link suddenly has three clones in different coloured tunics, and it turns out the sword is called the Four Sword and splitting its wielder into four is its power. You’d think they’d put a warning label on it, or something.

Now, with three other guys to help Link shoulder the blame for unleashing evil, he goes off to fix his mistake and save Hyrule. Ganon shows up along the way, at this point it’s probably not even out of malice, just a sense of obligation, and voila, it’s a Zelda story. I’m aware that my phrasing might come off a little patronizing of the writers, tough I mean it to be anything but. In fact, I’m impressed at how much mileage Nintendo has gotten from the, “Zelda gets captured/incapacitated and Link must save her and/or Hyrule” premise. It’s not as though they fall back on that for every game, Majora’s Mask and Link’s Awakening, for instance, have nothing to do with Zelda herself. Furthermore, there’s also usually either a twist on the formula (like the whole Four Sword thing), or they add in lore and side plots along the way to spice it up. In fairness, as I said before, it’s not an RPG game (Kinda like Illusion of Gaia, which falls somewhere in the middle, which I also reviewed), where story is as integral to the enjoyment of the game as the exploring and battling. Zelda games are almost always classified as Action-Adventure games. As a genre as a whole, they can have intriguing, heavy plots, but it’s not a genre requirement.

In that vein, Nintendo’s approach to Zelda is much the same as it is with many of their other franchises, like Super Mario, Metroid, and Kirby, in that it doesn’t try to reinvent the wheel with its story. I mean, they don’t need to. Think about it: how many Mario games are just, “Bowser kidnapped Princess Peach again,” and how many Metroid games are just, “Samus purposefully or unintentionally arrives on a strange planet and encounters either Metroids or other lifeforms that try to kill her”? Most of ‘em, right? That’s because it’s the gameplay that Nintendo relies on most heavily to market their games. For many gamers, especially parents my age who grew up with Mario and Zelda, they know what they and their kids are getting, and it’s a good fun courtesy of Nintendo. It doesn’t need to be The Lord of the Rings or Dune or The Gold & Steel Saga (What? I can’t plug my own books?), and that’s fine.

Much like Joanne Fluke and her cosy mystery stories, Nintendo has carved its niche in the comfort zone. They want players to know exactly what they’re getting with their new purchase or at least be confident enough that it’s going to be similar to what they’ve come to expect. They do take risks from time to time, to be sure. Majora’s Mask, once again, for instance. They set a standard with Zelda in the 3D era on the Nintendo 64 with Ocarina of Time, but Majora’s Mask, while using the same engine and assets, went in a starkly different direction in terms of plot and the time mechanics. Super Mario RPG on the SNES is another example, as it was a risk to put Mario in an RPG game when fans of both Mario and RPGs were used to that series being a platformer. While both paid off for Nintendo and were critical and commercial successes, they remain outliers in Nintendo’s general approach to making games.

Even Four Swords Adventures, with its multiplayer gimmick and the expensive hardware requirements to fully realize that gimmick, was a diversion from the norm for Nintendo. A simplified, textbook storyline, by that measure, was probably a calculation Nintendo carefully took when assessing the risks of releasing such a game. Along with that, the whole retro approach Nintendo took to Four Swords Adventures was a risk in and of itself at that time. Remember, this was 2004. At that point, most companies publishing on home consoles were trying to find and push the limits of what the GameCube, X-Box, and PlayStation 2 could do. Everyone wanted bigger, badder, and better games that looked as good as they played and kept the entertainment going for prolonged periods. Games needed higher polygon counts, in full 3D to appease the market at the time. I’m talking stuff like Spider-Man 2, Grand Theft Auto: Vice City, Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind, Halo 2, and Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic. Those were the games that were setting the bar, and retro, 2D games were passé, with cartridge console games selling on the used market for fractions of what you’d pay for them today.

If you’re a younger reader who isn’t old enough to remember those days, it’s probably hard to fathom that in 2024. We live in a time when gaming companies are cashing in hard on nostalgia to appeal to the millennial generation of gamers that grew up on that. You have independent companies rolling out retro-mimicking games like RetroMania Wrestling, Sea of Stars, and Undertale, whose developers freely admit to heavy influence from WWF WrestleFest, Chrono Trigger, and Earthbound respectively. Other indy devs go more for aesthetics like those seen in Untitled Goose Game, Human Fall Flat, Dredge, and Dave the Diver, games that dial back the graphics to harken players to late 2D and early 3D eras. Meanwhile, the big names have gone wild in the last decade making portable emulator “mini-consoles” featuring roms of old games, and they’re busy doing remakes and releases of the old games that brought them to the table in the first place. Even Nintendo have gone that route, remaking two games I’ve mentioned already: Link’s Awakening and Super Mario RPG.

Back then, though, just going for a look that might have been out of style was a risk, but one that again, paid off modestly for Nintendo (by their standards). The game racked up high-starring reviews across the board, clocked in as the third best-selling game in June of 2004, and registered 250,000 sold units over the course of its production.

Even now, Nintendo are still taking risks and trying new things. Look no further than the newest Legend of Zelda title: Echoes of Wisdom, which has eschewed Link in favour of letting Zelda have her first shot at being the main character in the games bearing her name.

The big question though, and to steer this article towards its conclusion: how does The Four Swords Adventures all come together as a whole package? In a word: excellently. People can and do question Nintendo’s business decisions. Stuff like the odd hoops developers often had to jump through to publish on the NES and N64, sticking with cartridges over discs for the N64, choosing mini-disks for the GameCube over DVDs, motion controls for the Wii, all that aforementioned risk aversion in game development, and so forth, have been regular debate points for years. Game fans have been arguing over that since video games and magazines dedicated to them hit the mainstream. However, no one questions Nintendo’s ability to make some of the best games of any video game era that they’ve been a part of. There’s no doubt that it’s a hassle and a half to even consider putting together the hardware to play Four Swords Adventures in multi-player these days. Heck, it would have been a headache when the GameCube and Game Boy Advance were still being produced and regularly used, let alone twenty years on since the game’s release. Yet, for all of that, I still maintain that if nothing else, Four Swords Adventures is worth playing in single player mode.

For A Link to the Past and Link’s Awakening fans, it scratches those itches, even if it does so in a roundabout sort of way with its levels and stages. For parents looking for games from their era to introduce to kids today, it has some challenge to it, but the fact that everything you’ll need is right there with you in any given level mitigates most of the potential frustration, and its brightly coloured aesthetics have a timeless appeal. The only downside might be price, as these days (as of Sept of ’24) the going rate for a loose copy (disk only) is about $63 (that’s about $85 in CDN for my fellow Canadians) and a complete copy (game, case, and manual) goes for about $75 USD ($100 CDN). If you don’t already have a GameCube, you might not want to fork out money for both the game and the console (not even getting into the cost of Game Boy Advances and link cables if you want multi-player). It’s hard for me to say if it’s worth that money. I paid a little less for my copy, but I did feel that I got my money’s worth as it’s a fantastic game with tremendous replay value. However, what you, the reader may find valuable will almost certainly vary from my definition.

That’s it for another review, and the first in quite some time. I took a sabbatical from writing in general for some time, and this is my attempt to try and get back into something I used to love. Feel free to comment below or anywhere that you find me posting this piece across social media. As always, if you have something you’d like me to review, let me know in those same comments or feel free to email goldandsteelsaga “at” gmail dot com. (I write it like that to throw off bots and webcrawlers).

Take care and stay safe!

Some images sourced from GameFaqs.com and Mobygames.com

Remember, if you like what I write, I’m an author of a little fantasy series too. Get them from Amazon right here. If you want to give back in another way, we also have a Buy Me a Coffee.

The sail on Z? Madness.

LikeLike